Theory of Relativity (Part 02)

The previous post delved into the Lorentz transformation, derived from the fundamental postulates of Special Relativity. This transformation leads to some counter-intuitive yet well-founded corollaries, such as length contraction and time dilation.

The Lorentz transformation is expressed by the following formula:

\[\begin{cases} x' = \gamma (x - vt) \\ y' = y \\ z' = z \\ t' = \gamma \left(t - \frac{vx}{c^2}\right) \\ \end{cases}\]where

- $v$ is the velocity of frame $F’$ relative to frame $F$.

- $\gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}}}$ is the Lorentz factor.

1. Relativity of simultaneity

From the Lorentz transformation, we can find that two separate events may not occur simultaneously in all inertial frames. This unusual phenomenon can be better understood through the following thought experiment.

Assume there are two light sources $S_1(x_1 = +x)$ and $S_2(x_2 = -x)$, and they are both turned on at $t = t’ = 0$. Then, for the observer $O$ in frame $F$, he sees the light from them appear simultaneously at $t = \frac{x}{c}$. Since the observer is at the midpoint between both sources, he is equidistant to them. In addition, light always travels at a constant speed ($c$), therefore he can conclude that they were turned on at the same time.

However, for the observer $O’$ in frame $F’$, everything is a little different. Since we consider the events that sources were turned on, we only need to know where these events happened in frame $F’$, not the velocity of the sources themselves. Therefore, we can omit the velocity of the sources. Then, in frame $F$ at $t = 0$, both observers $O$ and $O’$ are at the midpoint between the positions where the sources were turned on. Thus, in frame $F’$ at $t’ = 0$, the observers are also at the midpoint between the positions, so the observer $O’$ is equidistant to the positions. Once again light always travels at a constant speed ($c$), this implies that the events occurred simultaneously in frame $F’$ if and only if the observer $O’$ sees the light at the same time.

In practice, the light from the source $S_1$ reaches the observer $O’$ first, then meets the light from the source $S_2$ and the observer $O$ simultaneously. In other words, the observer $O’$ saw the light from the source $S_1$ before the light from the source $S_2$. This demonstrates that the events of the sources being turned on were not simultaneous in frame $F’$.

As shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, each observer perceives the simultaneity of the same events differently. They can see two events happened simultaneously (in the case of $O$) or not (in the case of $O’$). It is also noted that $S_1$ and $S_2$ in two figures represent only the positions where the sources were turned on, and these sources may move to somewhere afterward.

In conclusion, simultaneity is relative.

2. Length contraction

To measure the length of an object, we simply measure the distance between its two endpoints at the same time. However, as discussed in Section 1, the concept of simultaneity is relative. Therefore, we need to clarify how we measure the length of an object in this context.

Assume there is an object that is stationary and unchanged in frame $F’$. Then, the observer $O’$ always measures its length as $\Delta x’$ along the $x’$-axis whenever he takes a measurement. However, for the observer $O$, the frame $F’$ is moving, and so is the object. Therefore, when the observer $O$ measures the length of the object, he must measure the distance between its two endpoints simultaneously (of course in frame $F$).

Let $\Delta x$ be the length of the object measured by the observer $O$. From the Lorentz transformation, we have the following equation:

\[\Delta x' = \gamma (\Delta x - v \Delta t)\]The observer $O$ takes the measurement simultaneously in frame $F$, so $\Delta t = 0$. It implies that:

\[\Delta x = \frac{1}{\gamma} \Delta x'\]It should be noted that $\Delta x’$ is the true length and $\Delta x$ is the length we observe. Therefore, for an object with length $l$ moving with velocity $v$, we measure its length as $\frac{1}{\gamma} l$.

Moreover, $\frac{1}{\gamma} = \sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}} < 1$, so $\frac{1}{\gamma} l < l $. In other words, length undergoes contraction.

Another interesting point is that if we attach many identical clocks to the object, then when we measure its length, the clocks at the two endpoints cannot show the same time. That is due to the relativity of simultaneity, which is discussed in detail in Section 1.

3. Time dilation

The length can be changed, and so can the time. Of course, we also need to make clear how the time changes, similar to the way how we addressed the change in length (see Section 2).

Assume both the observers $O$ and $O’$ have identical clocks. That means if the clocks are stationary, they will always show the same duration. However, in practice, the clock of $O$ is stationary in frame $F$, while the one of $O’$ is stationary in frame $F’$. First, $O$ observes the clock of $O’$. After the duration of $\Delta t$, $O$ observes it again and notes that it shows the duration of $\Delta t’$. It is also noted that the clock of $O’$ is stationary in frame $F’$, so $\Delta x’ = 0$. Then, from the Lorentz transformation, we have the following equations:

\[\begin{aligned} & \begin{cases} 0 = \Delta x' = \gamma (\Delta x - v \Delta t) \\ \Delta t' = \gamma \left(\Delta t - \frac{v \Delta x}{c^2}\right) \\ \end{cases} \\ \implies & \Delta t' = \frac{1}{\gamma} \Delta t \end{aligned}\]As shown in Section 2, $\frac{1}{\gamma} < 1$, so $\Delta t’ < \Delta t$. Remember that $\Delta t’$ represents the passage of time in frame $F’$, while $\Delta t$ represents the passage of time in frame $F$. Therefore, $\Delta t’ < \Delta t$ means that things in frame $F’$, from the viewpoint of $O$, occur more slowly compared to those in frame $F$. In other words, time undergoes dilation.

However, all the processes we discussed above are from the perspective of the observer $O$. For the observer $O’$, they are quite strange. The observer $O’$ should see things in frame $F$ occurring faster compared to those in frame $F’$, but in practice, the opposite happens. Both the observers $O$ and $O’$ see time dilation in moving frames, which sounds like a paradox.

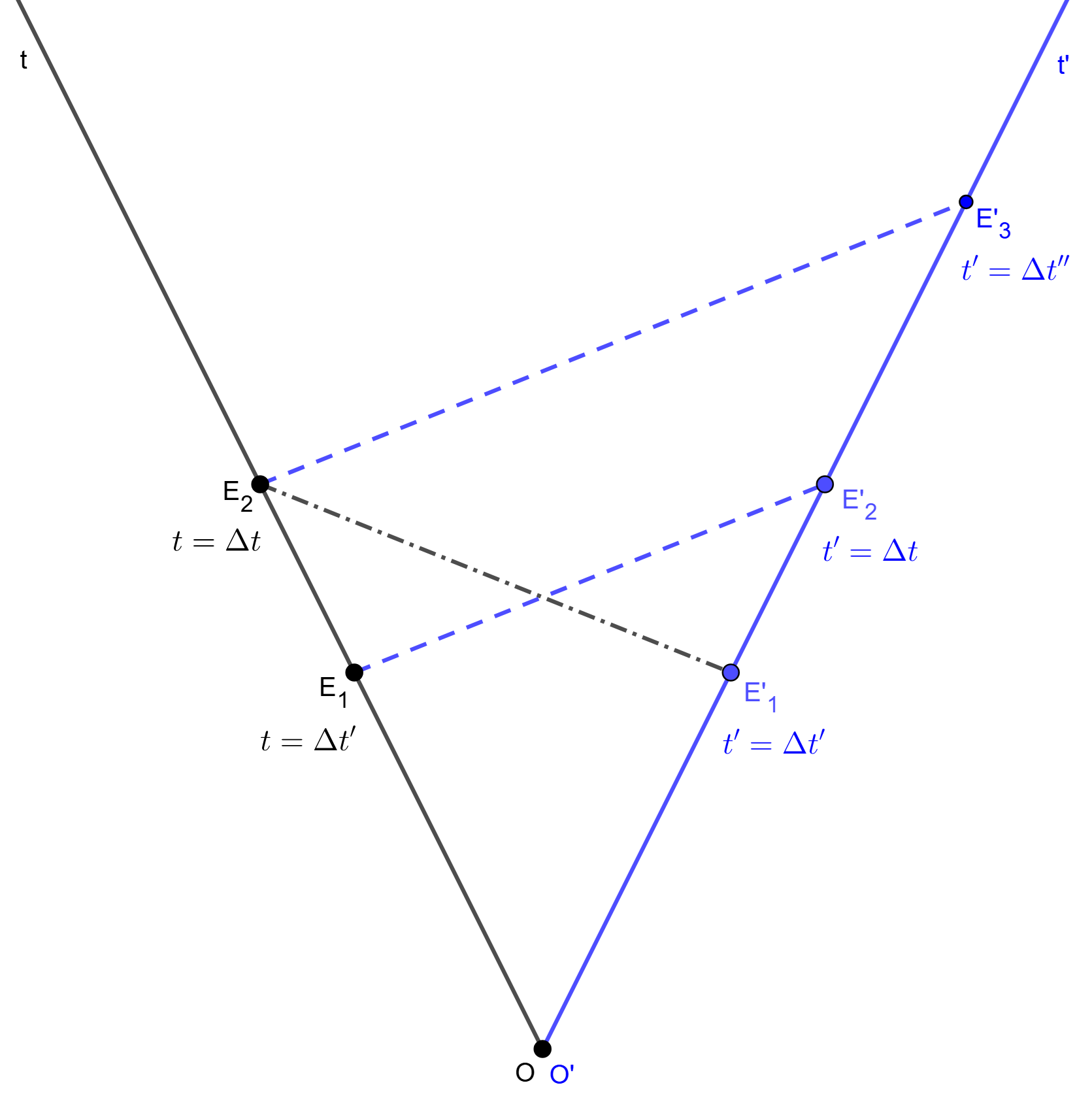

In essence, the above paradox can be explained by the phenomenon of relative simultaneity (see Section 1) as follows. In Figure 3, from the perspective of the observer $O$, the events $E_2(x_2 = 0, t_2 = \Delta t)$ and $E’_1(x’_1 = 0, t’_1 = \Delta t’)$ occur simultaneously. However, simultaneity is relative, so the observer $O’$ does not necessarily see that. Similarly, for the observer $O’$, the events $E_1(x_1 = 0, t_1 = \Delta t’)$ and $E’_2(x’_2 = 0, t’_2 = \Delta t)$ occur simultaneously, but not for the observer $O$. In conclusion, depending on the perspective of the observers, the event $E_2(x_2 = 0, t_2 = \Delta t)$ can occur simultaneously with the event $E’_1(x’_1 = 0, t’_1 = \Delta t’)$ (with respect to $O$) or the event $E’_3(x’_3 = 0, t’_3 = \Delta t’’)$ (with respect to $O’$). That explains the strange contradiction in time dilation.

4. Paradox of causality

In the last section of this post, we discuss a paradox related to causality. As mentioned in Section 1, the order of events can differ depending on the motion of the observer. In Figure 4, there are three cases: $A \to B \to C$, $C \to B \to A$, or even all three events occurring simultaneously. So, if $A$ causes $B$, and $B$ causes $C$, then $C \to B \to A$ implies that the consequential events can appear to occur before the causal events from the perspective of the observer. In other words, he can see the sequence of events in reverse chronological order. Is this (the paradox of causality) possible?

Assume that event $A$ causes event $B$. For simplicity, let $y_A = z_A = y_B = z_B = 0$. Then, $x_A = x_1$, $t_A = t_1$, $x_B = x_2$, and $t_B = t_2$.

We know that event $A$ causes event $B$, so $t_1 < t_2$. To prevent the paradox of causality, event $A$ must occur before event $B$ in any frame, i.e. $t’_1 < t’_2$ where $t’_1$ and $t’_2$ are, respectively, the times of event $A$ and event $B$ in the new frame. Then, from the Lorentz transformation, we have the following result:

\[\begin{aligned} & t'_1 < t'_2 \\ \iff & \gamma \left(t_1 - \frac{vx_1}{c^2}\right) < \gamma \left(t_2 - \frac{vx_2}{c^2}\right) \\ \iff & v (x_2 - x_1) < c^2 (t_2 - t_1) \\ \end{aligned}\]The above result is true for all $v$. It is also noted that $-c < v < c$ because of the Lorentz factor. Therefore, we implies that:

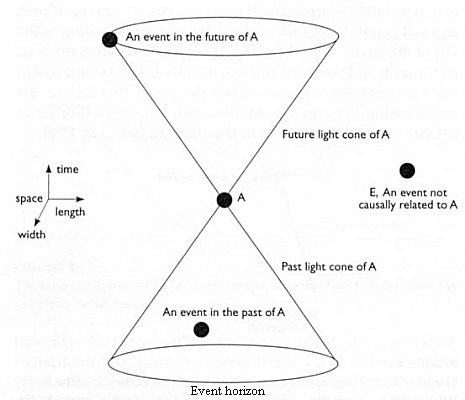

\[|x_2 - x_1| < c (t_2 - t_1)\]This means that the spatial distance between $A$ and $B$ is limited, and this limit depends on the temporal distance between on $A$ and $B$. So, all consequential events of an event must lie within a region of spacetime known as the future light cone. Similarly, all causal events of an event must lie within a region of spacetime known as the past light cone (see Figure 5).

So, in Figure 4, none of the three events lie within the light cones of the others. Therefore, there is no causal relationship between them, and the fact that no observer can see the sequence of events in reverse chronological order still holds true. Moreover, the above results also prove that faster-than-light communication is not possible because if it were, it would leads to the paradox of causality.

Comments

Or you can write comments directly on GitHub